This Sacred Art:

The Emergence of the Printed Book in Fifteenth-Century Europe

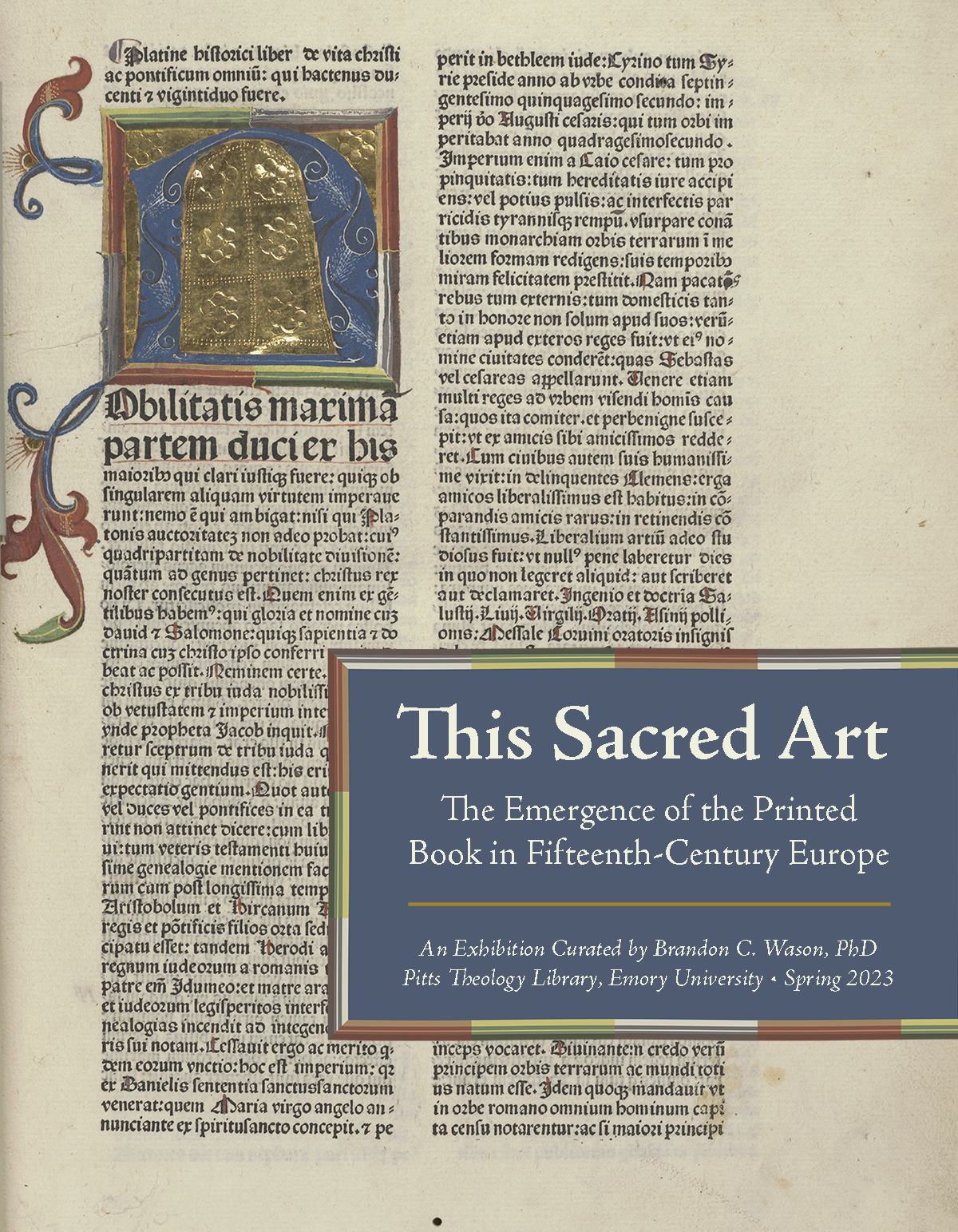

Illuminated page from the Letters of Saint Jerome

An illuminated page from the 1480 printed edition of the Letters of Saint Jerome. The illumination includes an initial letter "P" surrounded by floral decorations and surrounding an image of Saint Jerome holding a book. At the bottom of the page is an illumination showing a crest, which features a wolf, surrounded by a laurel wreath bound on the top, bottom, left, and right with decorative string. The illumination uses blue, red, green, brown, and black color with gold accents.Introduction

Johannes Gutenberg (circa 1400–1468) of Mainz, Germany, began printing with movable type in the middle of the fifteenth century. Though printing had already been in use throughout East Asia prior to Gutenberg’s inventive work, his introduction of printing to Europe had profound social and economic effects in the West. The art of printing proliferated during its first fifty years, and by the end of the fifteenth century about 30,000 separate works or editions had been printed throughout the continent. Books printed before 1501 are known as incunabula, meaning “in the cradle” of the printing press era. Contemporaneous accounts praised the advent of printing because books could be produced quicker, cheaper, and more accurately. More recently, scholars have described the introduction of printing in Europe as revolutionary because of the role it played in distributing and standardizing knowledge. This exhibition explores how printed books were made, decorated, and bound, as well as their content, the book trade, and the enduring influence of incunabula in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The title of the exhibition “This Sacred Art” is a translation of the Latin phrase haec sancta ars, which was used by Giovanni Andrea Bussi (1417–1475) in the preface to the 1468 edition of Jerome’s Epistolae, printed in Rome by Sweynheym and Pannartz.